Climate Change and Bees

Extreme Heat and its Effects on Bumble Bee Brood

The optimal temperature range for bumble bee brood—the eggs, larvae, and pupae developing in the nest—is 28–32°C. Worker bees regulate this by shivering to generate heat or fanning their wings to cool the nest. Temperatures above 36°C, however, are lethal. Research shows that even when more workers fan during heatwaves, these efforts usually fail to prevent overheating. Because brood development is essential for colony survival, extreme heat events increase the risk of colony collapse.[1]

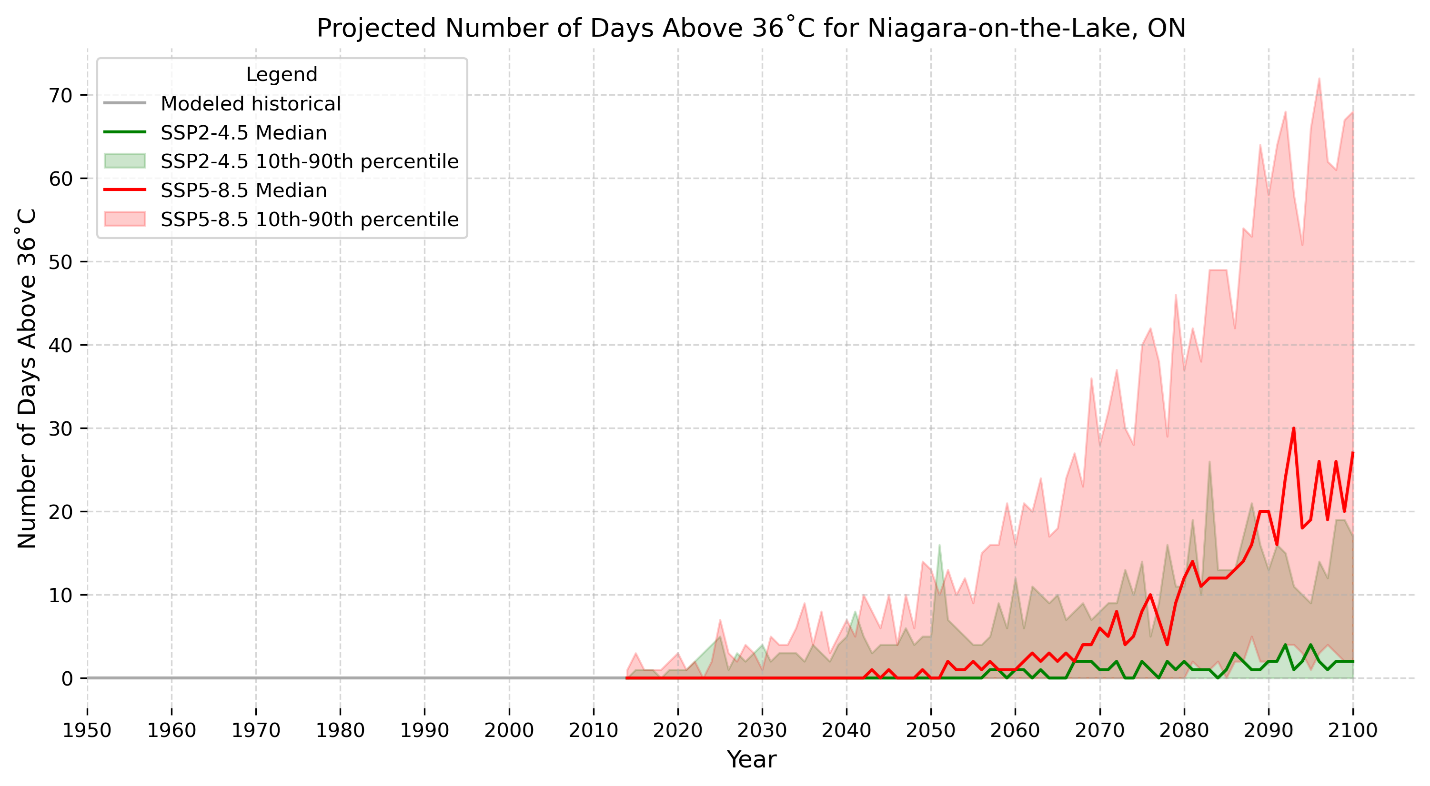

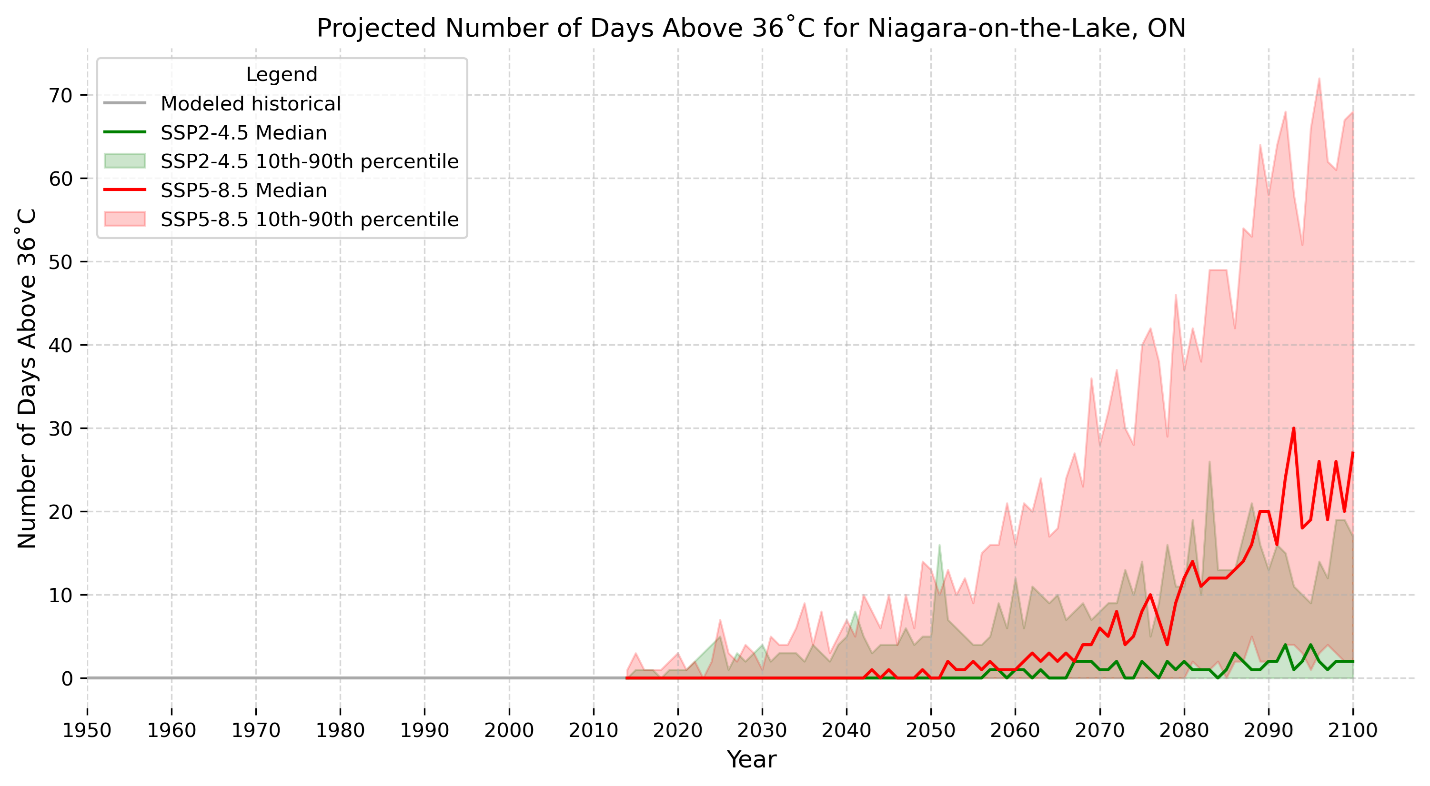

To illustrate these risks, we focus on Niagara-on-the-Lake, a small town in Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula known for its tourism, orchards, and wineries. We examined the number of days when maximum daily air temperatures are projected to exceed 36°C. Although this threshold refers to nest temperature, extreme ambient temperatures strongly influence nest conditions, and research shows that bumble bees often cannot prevent overheating during heatwaves. Air temperature therefore provides a reasonable proxy for estimating the risk to brood survival.

Figure 1: The projected number of days per year with daily maximum temperature exceeding 36°C near Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario under a medium (SSP2-4.5) and a very high (SSP5-8.5) emissions scenario.

Historically, days with maximum temperatures above 36°C have been extremely rare in this region. Climate models, however, project that by the end of this century the median could exceed 20 days per year under a very high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5). Under a medium emissions scenario (SSP2-4.5), the frequency is projected to be much lower—underscoring the role of mitigation in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and limiting extreme heat risks.

Climate Change and Chill Comas

Extreme cold is also an important stressor for bumble bees. Although extreme cold days are generally projected to become less frequent as the climate warms, cold exposure, including sudden cold snaps and late-spring frosts, may still be possible in some regions. Scientists have established that bumble bees enter chill comas—a temporary state of paralysis during which their muscles stop functioning—in ambient temperatures of 3°C to 5°C. Chill comas are associated with a variety of problems. For instance, bumble bees are unable to fly in this state, leaving them vulnerable to predation. Moreover, due to neuromuscular failure, there is a loss of spiracle function, meaning they can no longer breathe properly.[2]

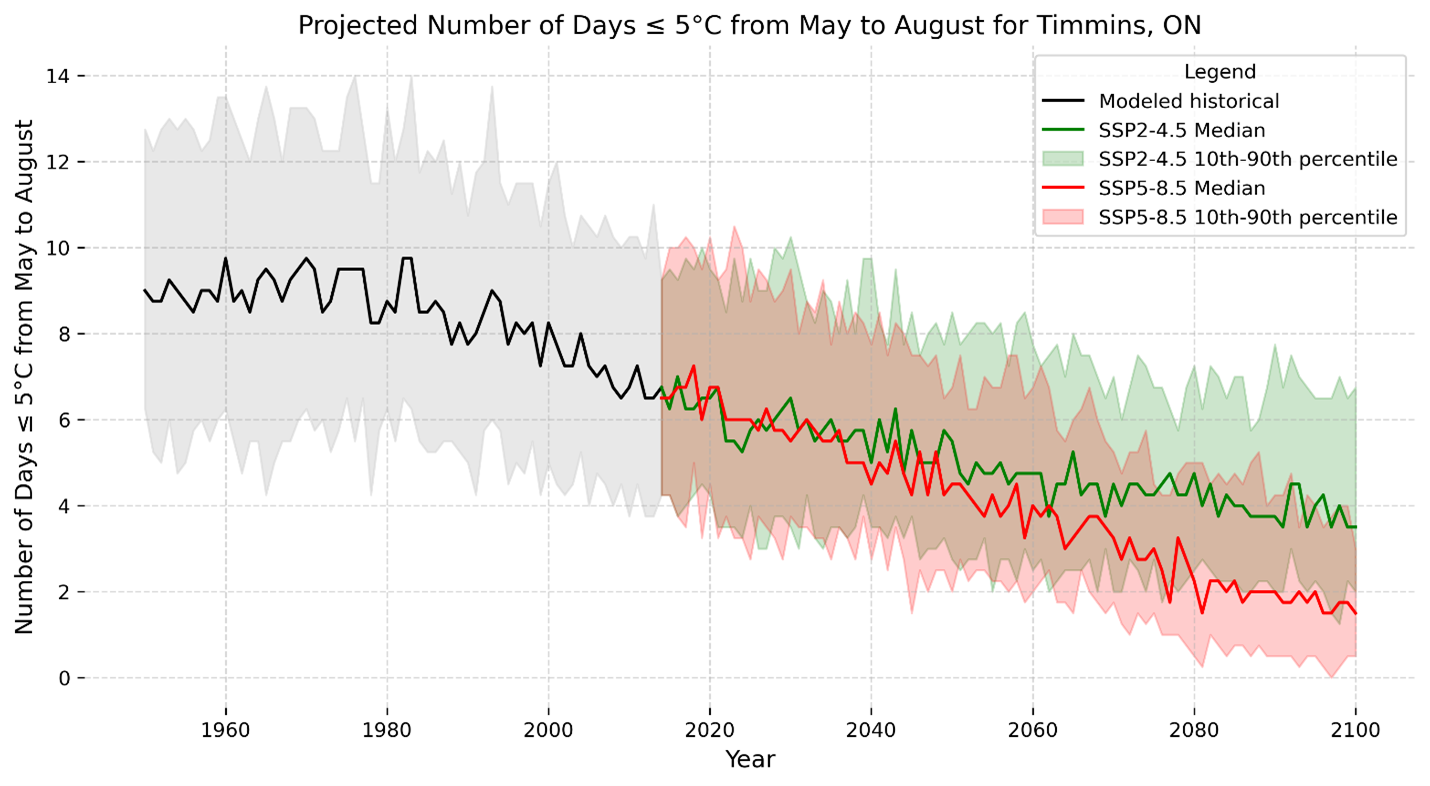

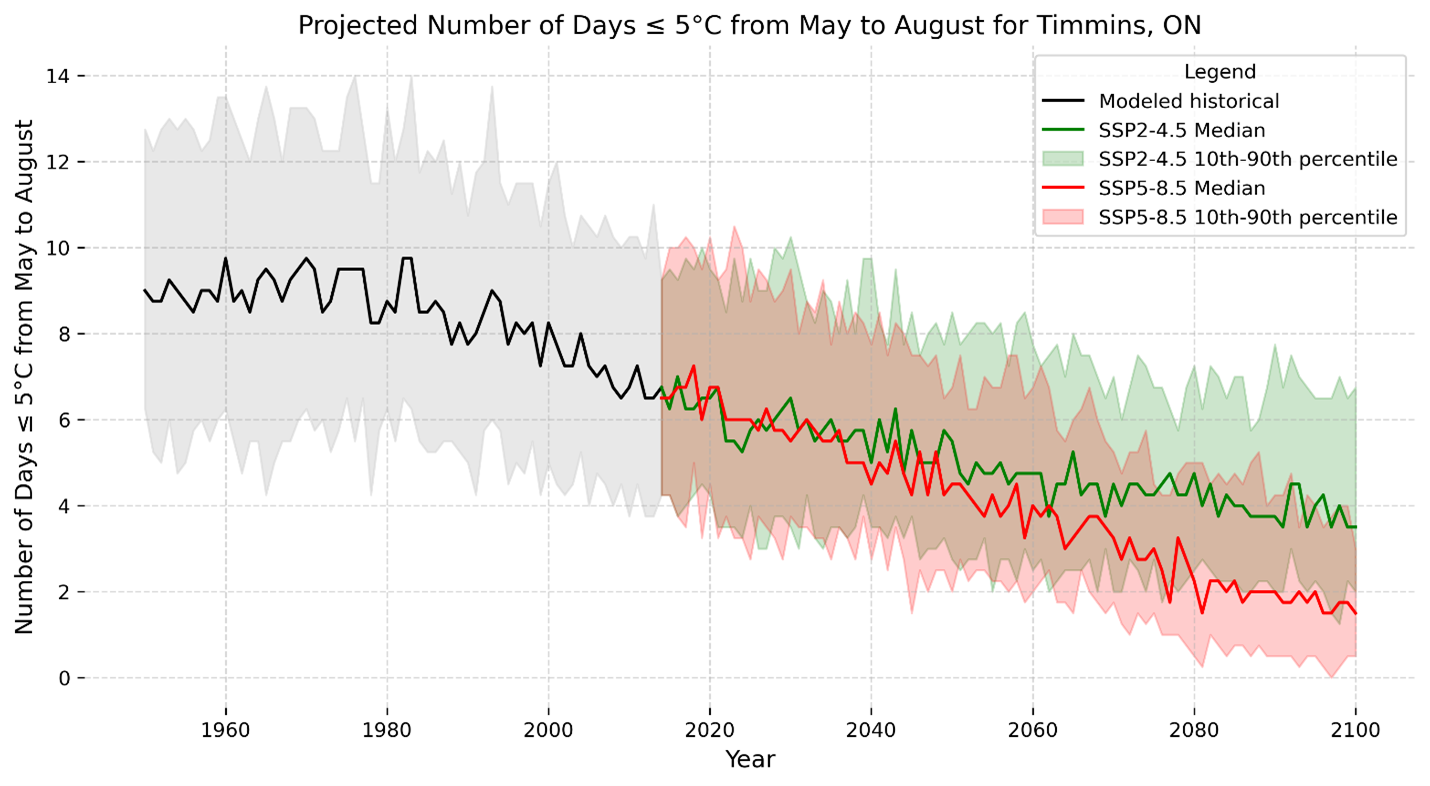

Timmins, Ontario, is a designated “Bee City.”[3] To explore potential climate stressors in this region, we used ClimateData.ca’s Download Page to examine the number of days from May through August from 1950 to 2100 with minimum daily temperatures of 5°C or lower. At this threshold, bumble bees can potentially enter a chill coma, reducing their ability to forage and care for the colony during the peak pollination season.

Figure 2: The projected number of days per year with minimum temperatures below or equal to 5°C during the summer season (May 1 to August 31) in Timmins, Ontario under a medium (SSP2-4.5) and a very high (SSP5-8.5) emissions scenario, from 1950 to 2100.

Overall, a warmer climate is projected to bring fewer days below or equal to 5°C during the summer season (May 1 to August 31) in Timmins, Ontario. Figure 2 shows that these “chill coma” days could decrease to as few as two per summer under a very high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5) and about four per summer under a medium scenario (SSP2-4.5) by 2100—roughly five to seven fewer days than historically observed. While this trend generally reduces the risk to bumble bees from cold summer days, it reflects long-term averages; sudden extreme cold events are still likely to occur and, even if less frequent, remain a hazard for bumble bees.

Taking Action

There are many actions that can support Canada’s bee population. For example:

- Avoid the use of pesticides and insecticides whenever possible.[4]

- Consider creating a pollinator-friendly garden, using plants native to the area. This will provide bees with a source of food.

- Create microclimates for bees by planting and maintaining habitat buffers such a hedgerows to provide bees with a respite from extreme heat.[5]

- Read more about preserving bumble bee populations by reading Bee City Canada’s comprehensive handbook here. Bee City Canada is an organization that works with communities to protect pollinators.

Conclusion

Climate change is altering the conditions that bees in Canada depend on to survive and thrive. Extreme heat can threaten brood survival, while cooler temperatures can limit foraging during critical pollination periods. These stressors compound existing pressures from pesticides, habitat loss, and disease, further increasing the challenges faced by both wild and managed bee populations. Tools available through ClimateData.ca can be used to inform assessments on how these climate stressors may change in the future. By examining projections of temperature extremes, farmers, policymakers, researchers, and communities can better anticipate risks and support adaptation strategies that help sustain bee populations—and the ecosystems and agricultural systems that depend on them.