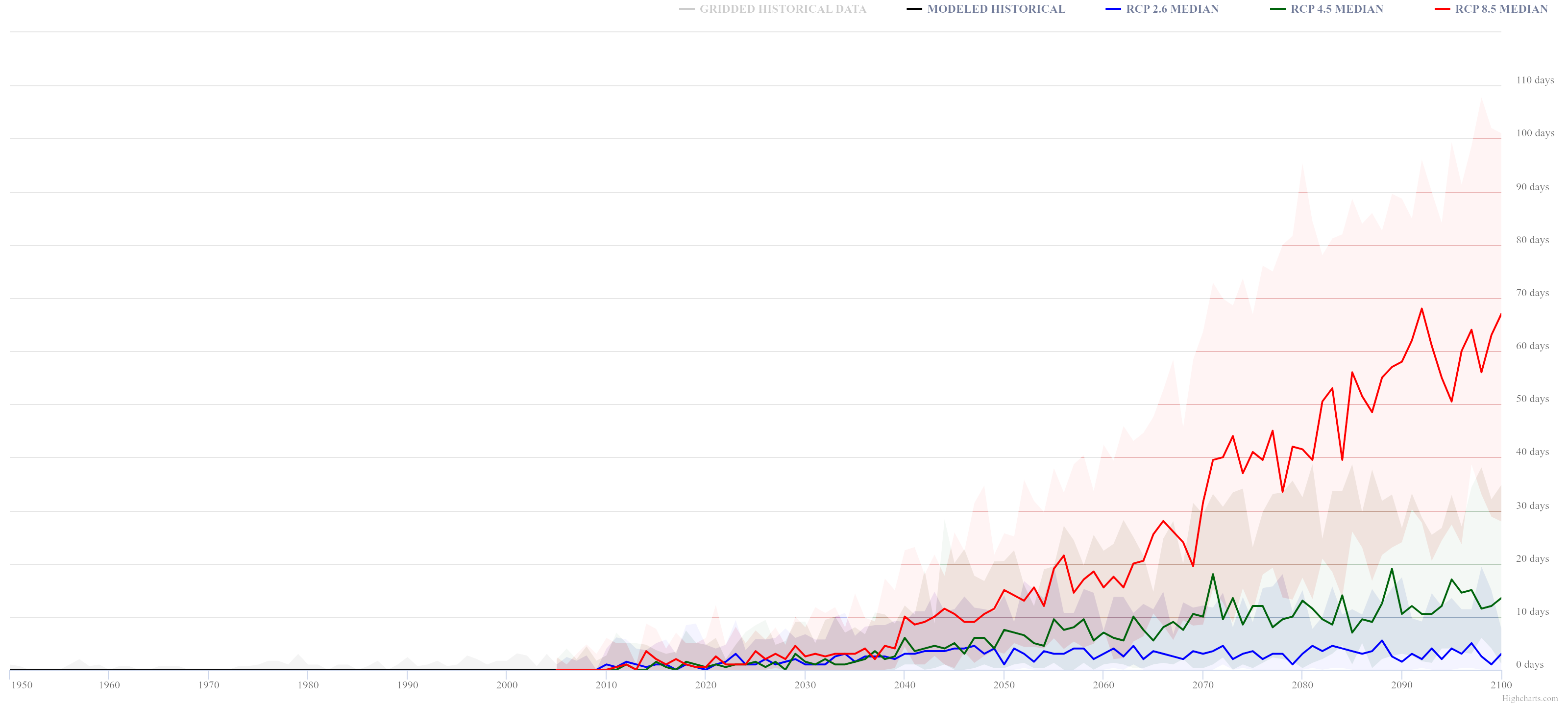

Annual number of tropical nights simulated over the 21st century by an ensemble of global climate models for a location within the Greater Vancouver area. Different colours refer to different future emissions pathways (RCPs), with heavy lines showing the multi-model median and lighter shading indicating the multi-model range. Hover your mouse over the figure to view projected changes to tropical nights over time, under three emissions scenarios.

This information is important for all developers and housing providers, including an organization like BC Housing, since their buildings will have a certain energy budget prescribed by local governments through the Step Code. As Leung explains, “Without adequate cooling provisions, in the future, people in those households will just go out and buy an off-the-shelf air-conditioner, stick it in their window, and now your energy budget is blown.”

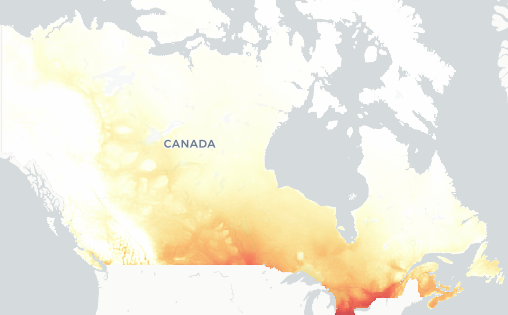

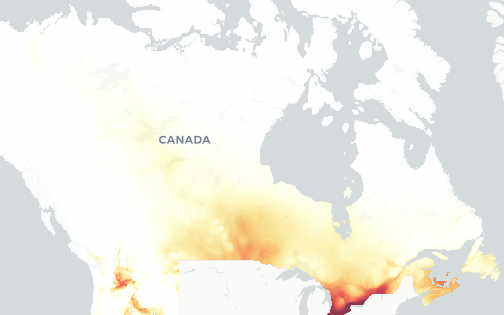

For this reason, BC Housing developed a series of guidelines to build with this in mind. The organization then reached out to the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium to calculate future-adjusted versions of location-specific, historical weather files at different periods in the future, using the high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5). Utilizing the high emissions scenario provides the most appropriate range of outputs for design, as the amount of climate change that would occur in the high emissions scenario by about mid-century is similar to what would occur under a mid-range scenario (RCP 4.5) later in the century. These “future-shifted weather files” constitute an educated guess of what typical daily temperatures might be at locations that already have historical weather files. BC Housing then used these files as inputs to energy models that simulated building performance under these warmer conditions, both for existing buildings and those currently being designed.

The next step was to conduct a more fine-grained analysis, moving from the entire building’s energy budget and performance to the level of individual units within a building. An individual unit’s overheating risk depends, among other things, on its orientation and location. One would expect that, for example, a southwest-facing unit might be more exposed to overheating than a unit in the northeast corner of the building.

“I’ve been working in this area for some time, but it was so surprising to find out when we did the energy modelling using future weather files, that a lot of our buildings that we had designed would be at very high risk of overheating the very first summer that the building opens,” says Szpala. “That was a bit of a shock. That was huge.”

Both Leung and Szpala say that if they were to advise other developers, the number one recommendation would be to consider overheating risk as early in the process as possible. At later stages of project development, incorporating climate adaptation measures is likely to be difficult and, consequently, expensive. “We definitely learned the hard way.”