Introduction

Hot weather affected Canadians across the country in 2025. Nationwide, it was the 11th warmest summer on record since 1948, reflecting long-term summer warming of 1.8°C over the past 78 years1. The on-the-ground experience, however, varied by region. Differences in the timing, duration, and intensity of strong heat waves influenced its impact on Canada’s healthcare systems, infrastructure, wildfire risk, and people’s daily lives. Regional-scale extreme heat events are becoming more common and severe due to human-caused climate change.

Extreme Heat, Heat Warnings, and Heat Waves

When temperatures are much hotter than usual for a particular place and time of year, it is generally called an “extreme heat event” or “heat wave”. For public health and emergency planning, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and health partners use specific heat warning criteria. These criteria look at how hot it is during the day, how little relief there is overnight, the duration of the exceptionally hot weather and, in some regions, how humidity adds to the heat stress (described by the Humidex).

When health-based thresholds are reached for two or more days in a row, ECCC and public health partners issue heat warnings and activate Heat Alert and Response Systems. These systems are designed to protect Canadians by triggering actions such as opening cooling centres, checking on vulnerable people, and sharing advice on how to stay safe.

The summer 2025 extreme heat events described in this article will be familiar to many people because they often coincided with heat warnings. However, the events analyzed here are defined slightly differently than those based on criteria for health-focused heat warnings. Specifically, the events below are characterized by daily maximum temperatures averaged over one of 17 regions across Canada exceeding the typical hottest day of the year for the region. Once characterized, the Rapid Extreme Weather Attribution system is used to determine whether human-caused climate change has changed the likelihood of these heat events occurring in these regions.

The Rapid Extreme Weather Attribution System

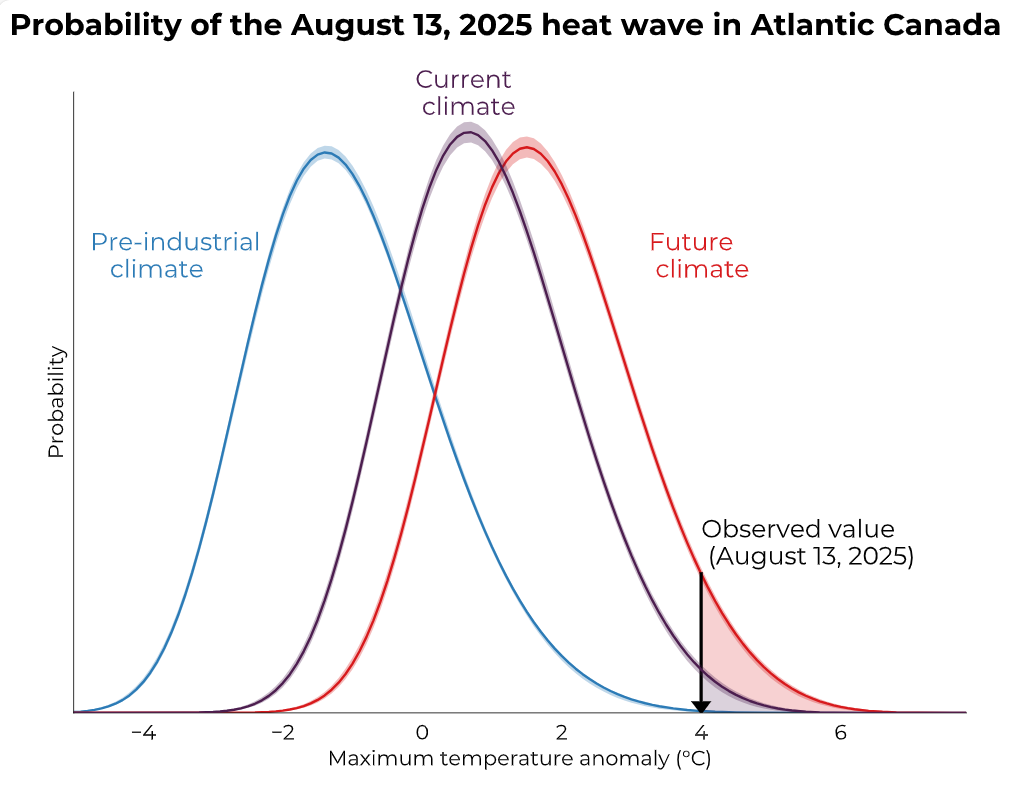

To understand how emissions generated by human activities directly impact extreme weather, such as heat events, scientists from the Climate Research Division at ECCC developed the Rapid Extreme Weather Event Attribution system. This system uses advanced climate models and observations to compare three climates: the pre-industrial conditions of the 1800s, today’s climate, and a projected future climate reflecting additional global warming. Immediately after an extreme event occurs, scientists can compare the likelihood of such an event happening in each of the three climates (pre-industrial, current, and future) and calculate the change in probability due to human-caused climate change. By providing insight into the causes and likelihood of extreme events, the Rapid Extreme Weather Event Attribution system allows for better planning related to weather emergencies, supports decision making to protect health, safety, and property, and informs climate change adaptation.

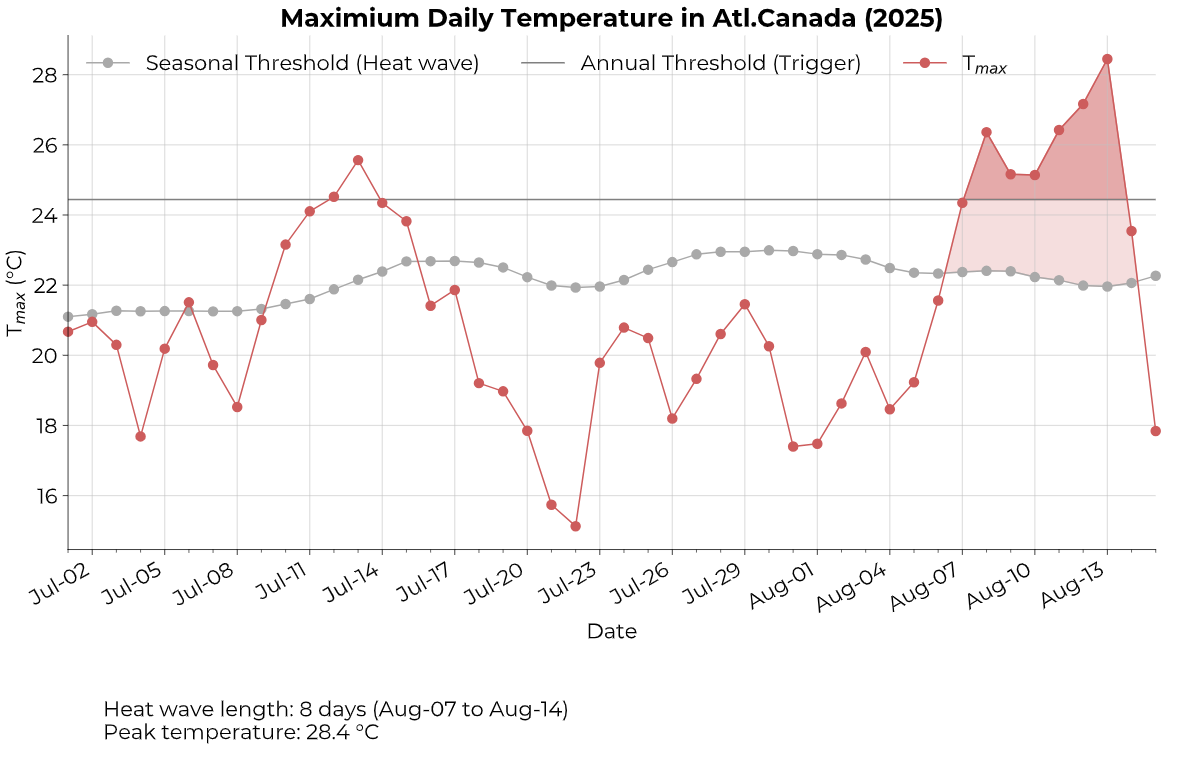

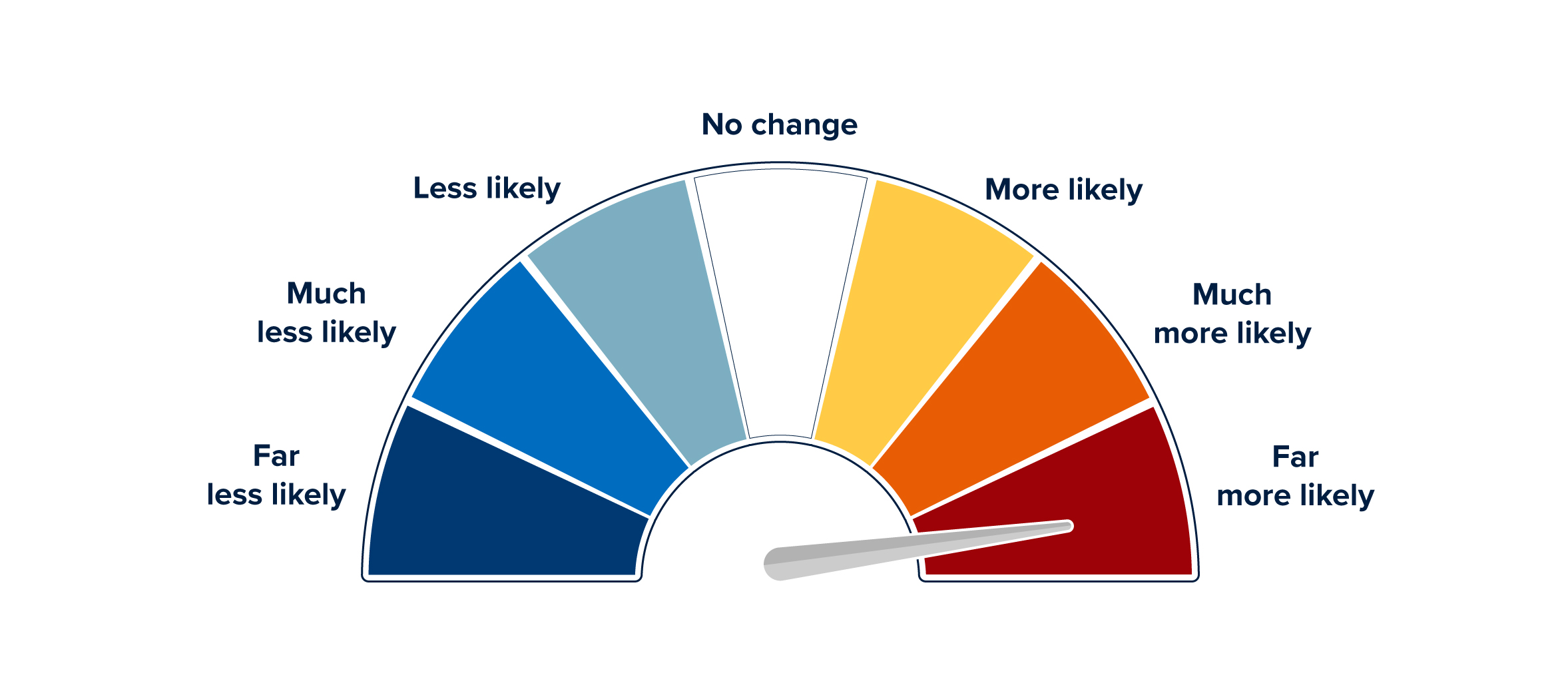

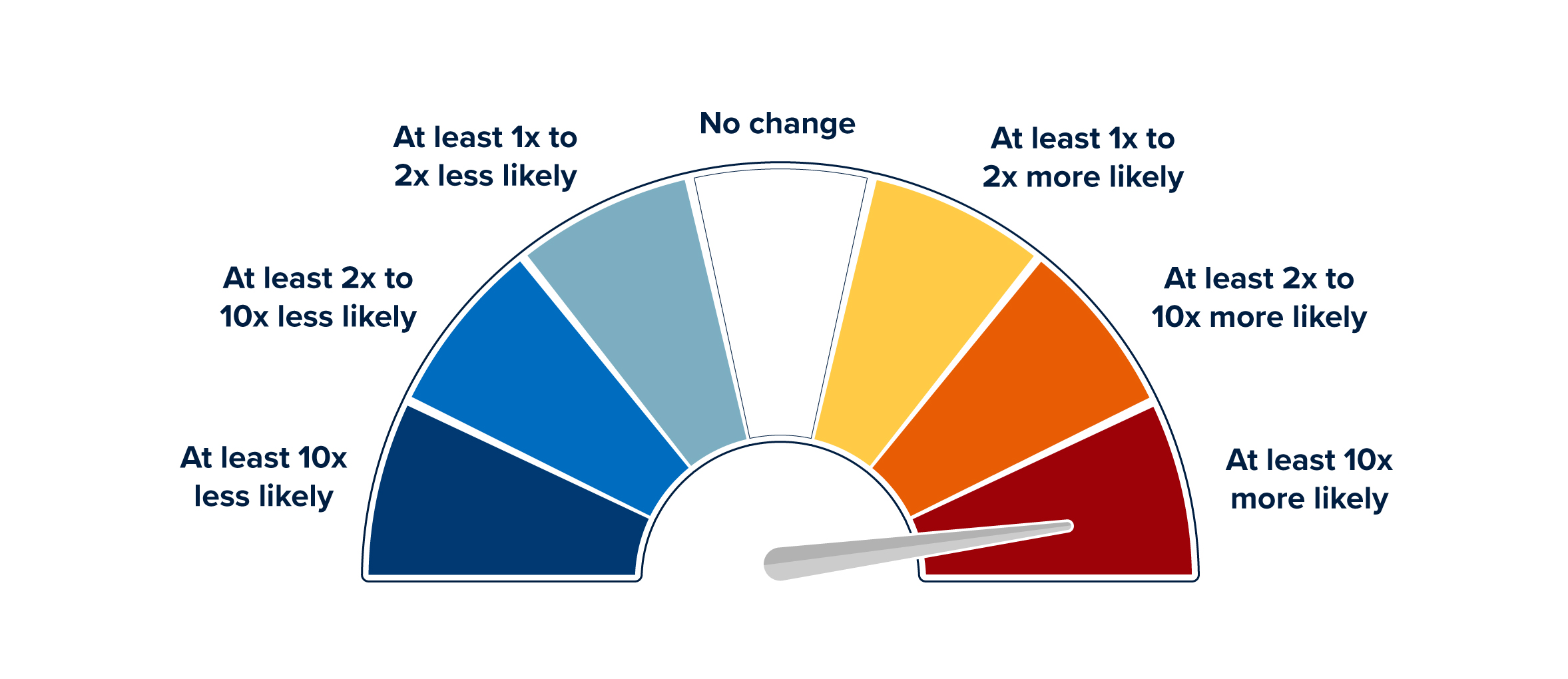

The Rapid Extreme Weather Event Attribution system divides Canada into 17 regions. The system runs every day and uses a trigger criterion based on an annual threshold of the typical hottest day of the year from a 1991-2020 base period to define heat events. When the daily maximum temperature (averaged over a region) exceeds the average annual maximum temperature for that region from 1991-2020, the system automatically identifies a heat event and calculates how human influence on the climate impacted the likelihood of the event*. The attribution analysis focuses on the peak temperature during the event, but to add relevant context, the duration of the event is defined based on a seasonal threshold of how many days exceeded the 90th percentile of daily maximum temperatures for that time of the year. Results are reported as a statement of likelihood on a scale ranging from far less likely to far more likely, with each statement corresponding to a probability/risk number value. For example, an event of a given magnitude determined to be much more likely in the current climate due to climate change is at least 2x to 10x more likely to occur in today’s climate compared to the pre-industrial climate of the 1800s.

Summer 2025 Heat Across Canada

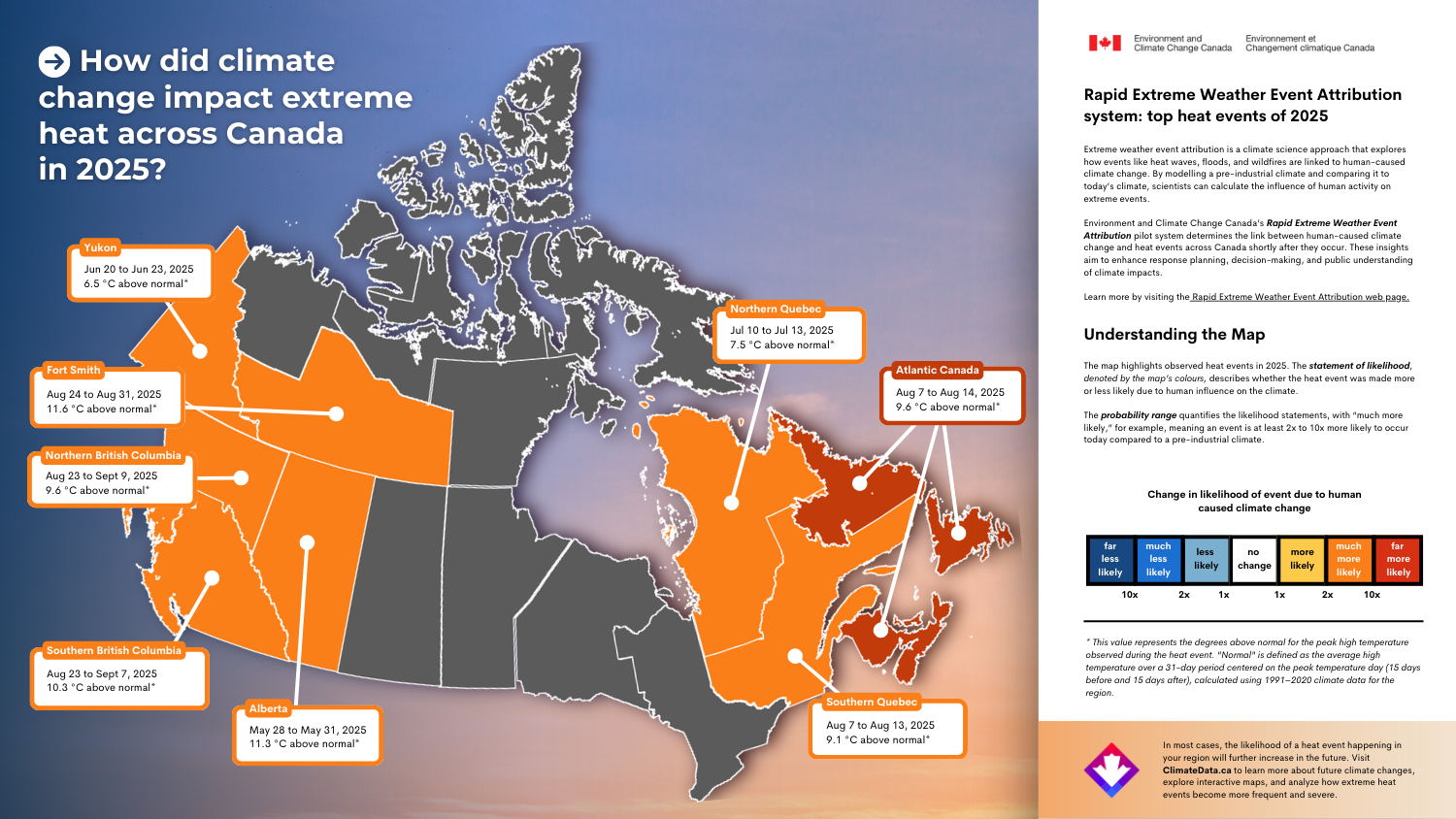

This past summer, human-caused climate change influenced heat events in many regions of Canada. A total of 12 heat waves were identified by the system, with 11 determined to be much more likely and one determined to be far more likely (at least 10x more likely) due to human-caused climate change. The map below shows the most extreme event identified for each region (eight events total because only the strongest event is shown for regions with more than one event; grey regions did not have a heat wave that met the criterion for a heat event set by the system).

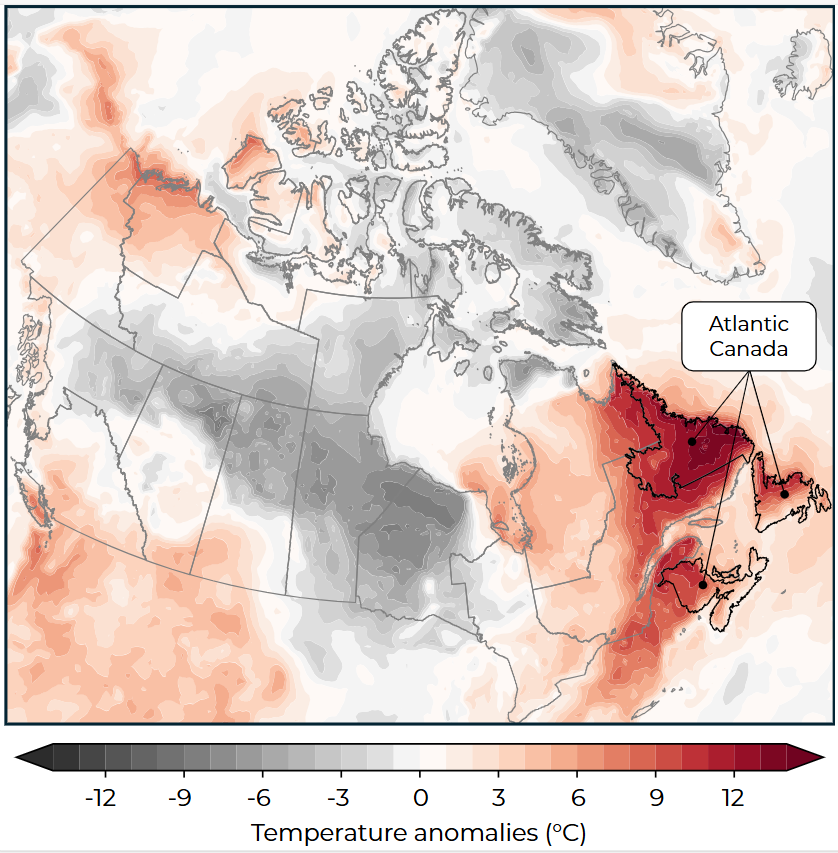

Notable heat events occurred in western Canada at the beginning and end of the summer season, with a surge of heat in late August and early September. Eastern Canada experienced a short but intense warm window later in the summer, with hot weather in mid-July and August, including an event in Atlantic Canada that had the strongest calculated human influence on likelihood of the 12 events. Northern Canada also experienced heat at the beginning and end of summer, with events in Yukon in June and in the Northwest Territories in late August.