Introduction

Parks Canada administers one of the most extensive networks of natural and cultural heritage places in the world. It includes 171 national historic sites, 47 national parks, five national marine conservation areas and one national urban park. In an era of rapid climate change and technological development, ensuring these sites and the values they hold for Canadians are resilient to shifting climate zones and increases in extreme weather is more important than ever. To this end, Parks Canada is working to better understand the evolving climate change risks and impacts at the sites it administers, and planning for actions that reduce climate vulnerabilities and enhance their protection.

Like many land, water and asset stewards, Parks Canada faces an enormous challenge when it comes to climate change. Indeed, climate change is expected to affect all of Parks Canada’s program areas—the conservation and protection of natural and cultural heritage, visitor experience, built assets, and the health, safety and wellness of visitors and staff. Shifting climate zones, wilder and less predictable weather, and record-breaking extreme events puts all of these systems at increased risk.

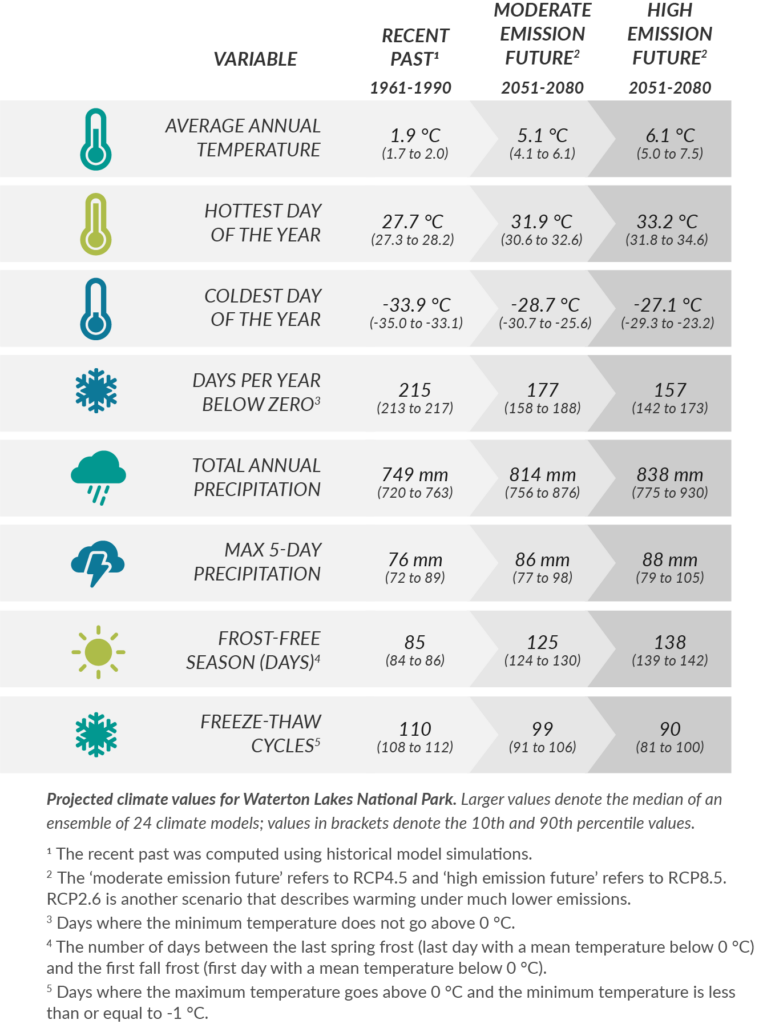

As part of a national effort to identify and address the risks associated with climate change, Parks Canada approached the Canadian Centre for Climate Services (CCCS) for help extracting relevant climate change data for trends and projections of key variables at each national park, national marine conservation area, and national historic site across Canada. This request turned into a larger collaboration between CCCS and Parks Canada’s Climate Change Science and Advisory Team, which focused not only on extracting data but also on making sense of how observed and projected changes in the climate translate into changes in the risks, vulnerabilities, and impacts to Parks Canada’s programming and operations across the country.

What to do with all these data?

Having climate change data available for every variable, year, scenario, and site is great, but these data alone do not speak to the risks, vulnerabilities, and impacts on operations and programming at sites administered by Parks Canada. A key next step in the process was for Parks Canada to engage with its local management teams, staff, and partners to raise awareness of and unpack these climate change data to distill their significance.

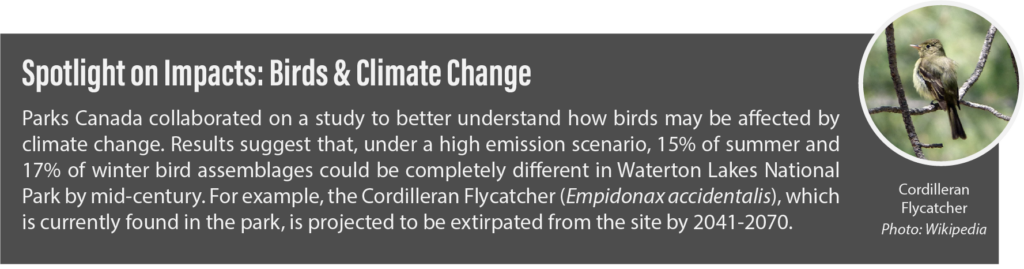

As expected, every site has its own perspectives and priorities when it comes to climate change, ranging from concerns over wildfire, sea-level rise, invasive species, permafrost thaw, changes in freshwater availability, and much, much more. Through these conversations, it is possible to develop a short-list of meaningful climate change metrics and to summarize key impacts and risks associated with their changes.

Moving from risk to resilience

Having identified key climate risks and vulnerabilities from these climate data and through engagement with local management teams and partners, Parks Canada’s Climate Change Science & Advisory Team was able to develop examples of potential adaptation responses that could be implemented at each site. The list of potential responses is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather serves as a starting point for a larger conversation and climate change adaptation planning efforts on the ground.

Next Steps

The need for sound climate data will only grow as the effects of climate change become more pronounced; data will be a crucial element for planning and management efforts of Parks Canada to fulfill its mandate to protect significant examples of natural and cultural heritage.

As Parks Canada works to lead the National Ecological Corridors program, and contribute to the government’s commitment to protect 25% of Canada’s lands and oceans by 2025 by establishing new National Parks, National Urban Parks, and National Marine Conservations Areas, the need for new data will emerge. This is also true for National Historic Sites, which will experience new and increasing climate change related risks and impacts. Collaborations between Parks Canada and the CCCS will help Parks Canada stay apprised of the latest data, especially in developing areas such as marine environments and fulfill its commitment to provide climate summaries to places and teams across the country.

Working Together

The Canadian Centre for Climate Services (CCCS) provides access to data and information as well as offers training and support on how to use climate information to support decisions that increase resilience to the impacts of climate change.

Canada.ca/climate-services

Acknowledgement

This article would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions made by the staff at Parks Canada. Thank you for providing your input and edits. Special thanks to everyone at the Office of the Chief Ecosystem scientist and Parks Canada Communications departments.