References

[1] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2024). Statistical Overview of the Canadian Ornamental Industry, 2024. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/sector/horticulture/reports/statistical-overview-canadian-ornamental-industry-2024

[2] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2024). Statistical Overview of the Canadian Ornamental Industry, 2024. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/sector/horticulture/reports/statistical-overview-canadian-ornamental-industry-2024

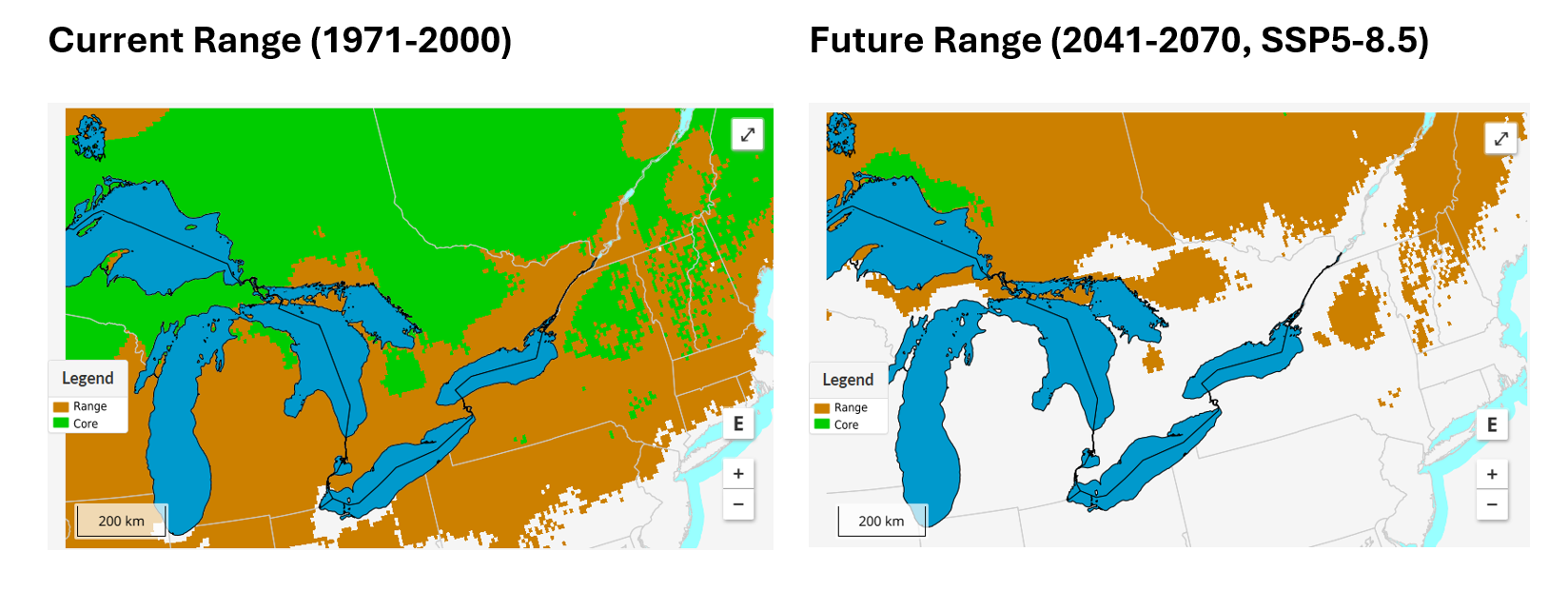

[3]Natural Resources Canada. (2025). Canada’s Plant Hardiness Site, Species-specific Models and Maps. Picea glauca (Moench) Voss. https://www.planthardiness.gc.ca/index.php?phz=p10007941971-2000&s=b&speciesid=1000794&m=7&lang=en#

[4] (2025). Canada’s Plant Hardiness Site, Species-specific Models and Maps. Picea glauca (Moench) Voss. https://www.planthardiness.gc.ca/index.php?phz=p10000051971-2000&s=b&speciesid=1000005&m=7&lang=en

[5] Koelling, M. R., Hailigmann, R. (1993). Recommended Species for Christmas Tree Plantings In the North Central United States. Forest Ecology and Management. https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/234/84938/Recommended_Species_for_Christmas_Tree_Plantings-optimized.pdf

[6] Andalo, C., Beaulieu, J., Bousquet, J. (2005). The impact of climate change on growth of local white spruce populations in Quebec, Canada. https://www.cef-cfr.ca/uploads/Colloque/LectureBeaulieu.pdf

[7] Still, C. J., et. al. (2023) Causes of widespread foliar damage from the June 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome: more heat than drought. Tree Physiology.

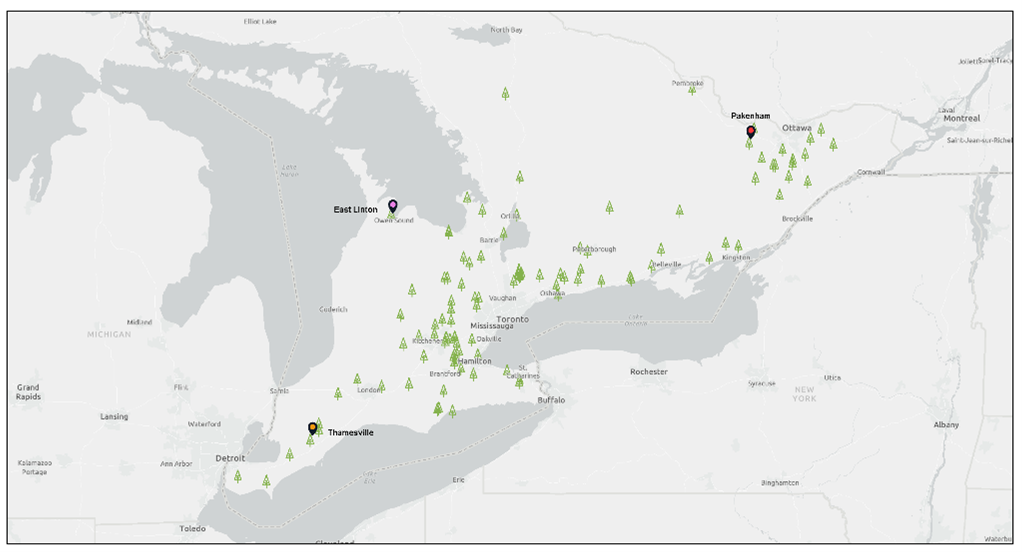

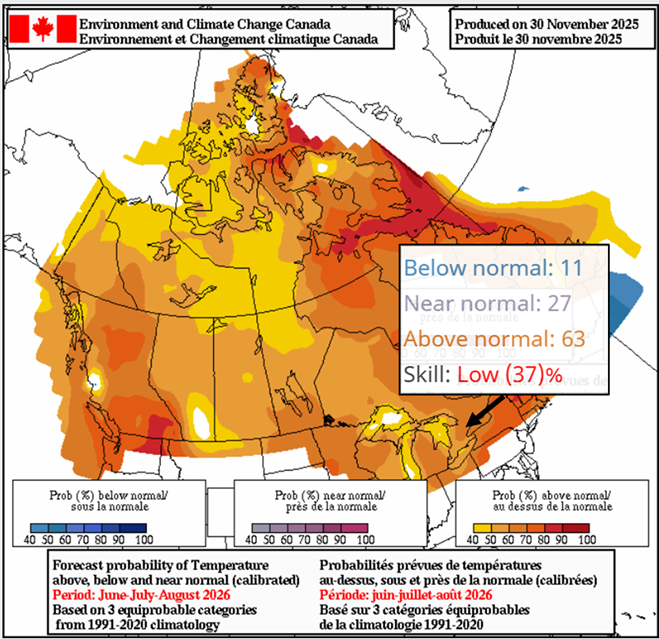

[8] Christmas Tree Lab. (2025) Protecting Ontario’s Christmas Tree Industry from Increasing Climate Change Risks. Waterloo Climate Institute Policy Brief. https://uwaterloo.ca/climate-institute/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/2025_policy-brief_leonard_final_compressed.pdf

[9] McCarthy, P. C., Adam, C. I. G. (2023) Insects and Diseases of Balsam Fir Christmas Trees. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/rncan-nrcan/Fo103-2-226-eng.pdf

[10] Ontario Crop Protection Hub. (n.d.) Degree-Day Modeling. Retrieved December 1, 2025 from https://cropprotectionhub.omafra.gov.on.ca/supporting-information/apples/pest-management/degree-day-modeling

[11] McCarthy, P. C., Adam, C. I. G. (2023) Insects and Diseases of Balsam Fir Christmas Trees. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/rncan-nrcan/Fo103-2-226-eng.pdf

[12] Fondren, K., McCullough, D. G., (2002) Biology and Management of Balsam Twig Aphid. Michigan State University Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/files/e2813.pdf

[13] Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Forest Pests and Climate Change. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/forest-pests-and-climate-change

[14] Christmas Tree Farmers of Ontario. (n.d.) Real Tree Facts. https://www.christmastrees.on.ca/index.php?action=display&cat=11