Ontario public health officials analyze Lyme disease risk by reporting all cases of Lyme disease, monitoring I. scapularis in its natural habitat, and keeping the population informed about the risk of infection.

For example, active tick surveillance activities were recently conducted in Ottawa5, Ontario. From June to October 2017, researchers collected tick samples using the drag sampling method in 23 sites including municipal parks, recreational trails and forests within the city of Ottawa. In total, almost 30% of the 239 I. scapularis ticks collected were infected with B. burgdorferi, known to cause Lyme disease.

A two-year study was also carried out in the Dundas area7, in which veterinarians and pet groomers were asked to collect blacklegged ticks from dogs and cats with no history of travel. Additionally, I. scapularis specimens were submitted from local residents and collected by marking. In total, 12 (41%) of the 29 blacklegged ticks collected were infected with B. burgdorferi, confirming the pathogen’s presence in the area.

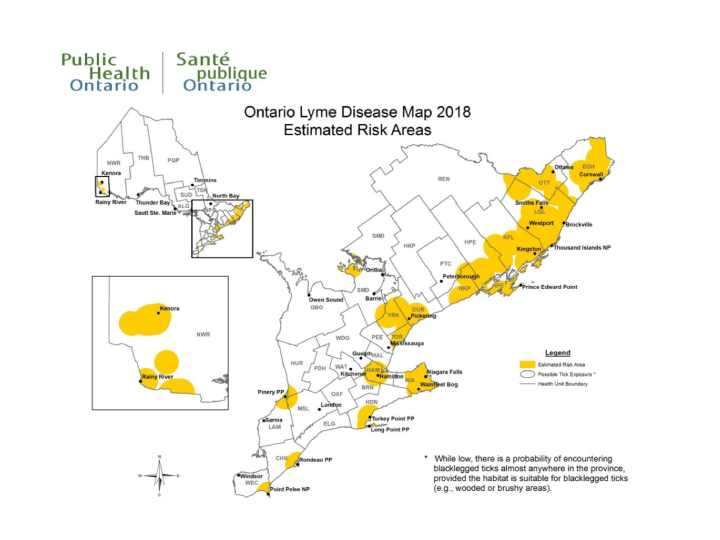

In addition, Public Health Ontario publishes an updated map (see Figure 2) every year identifying areas where blacklegged ticks are known to occur and where humans have the potential to come into contact with infected ticks. Estimated risk areas are calculated as a 20-km radius from the centre of a location where blacklegged ticks were found.

The purpose of the map is to assist local public health units with Lyme disease case investigations and to help health professionals evaluate the risk of infection among their patients. Public Health Ontario warns users, however, that blacklegged ticks are transported by migratory birds, meaning there is a possibility of encountering an infected blacklegged tick almost anywhere in Ontario.

Figure 2: Map of zones at risk in Ontario, summer 2018.

Each year Public Health Ontario publishes an updated map identifying the zones where the presence of black-legged ticks is known or where people may potentially come into contact with infected ticks. The estimated risk areas are calculated using a radius of 20km from the centre of the location where black-legged ticks were detected.