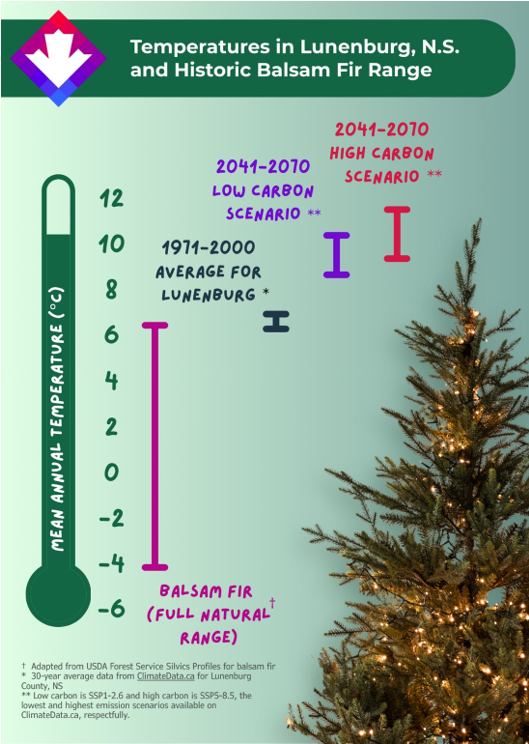

Take the balsam fir as an example. Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, recognized in 1995 as the ‘Balsam Fir Christmas Tree Capital of the World’, has long been known for producing high-quality balsam fir trees, a species indigenous to the region. [4]

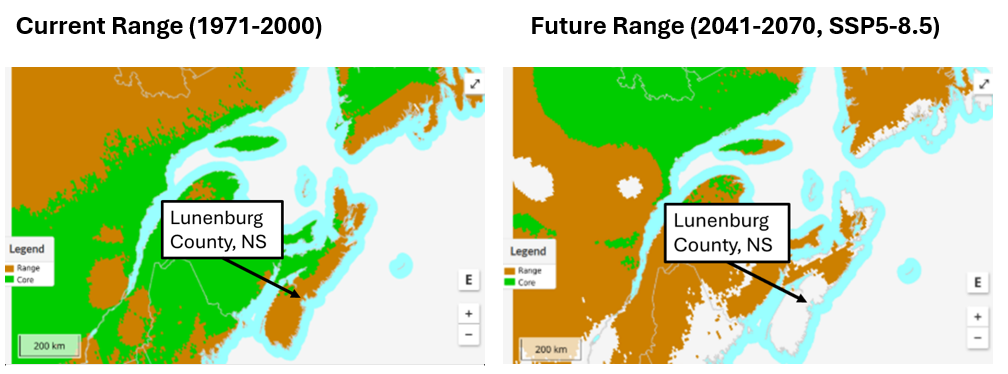

In Figure 1, the green area represents the ‘optimal’ or ‘core’ climate suitability range for balsam fir—the conditions under which the species tends to grow most vigorously across its natural distribution. The brown area indicates the full suitability range, where the species is still capable of surviving or being successfully cultivated, though growth may be slower or more variable. The panel on the right of Figure 1 shows the 1971–2000 native range of balsam fir, which extends across much of eastern Canada. In Lunenburg County, even in the recent past (1971-2000), the climate conditions are outside of the core (green) suitability range for balsam fir, though the conditions do fall within the full suitability (brown) range. Despite falling largely outside of the core range in recent history, balsam fir has thrived in Nova Scotia, due to local factors — such as abundant precipitation, moderate summer temperatures, and microclimates— that help offset conditions that are warmer or drier than the optimal range. Management practices, such as careful site selection and shading, also play a role in sustaining healthy crops outside of the species’ suitability range.

Looking ahead to 2041-2070, under a high-emissions scenario, the suitability range for balsam fir is projected to shift northward (the left panel of Figure 1). For parts of Nova Scotia, including Lunenburg County, future climate conditions are expected to fall outside of the species’ suitability range. This does not mean balsam fir will no longer grow there, but it does suggest that establishment and regeneration of this species may become more challenging, requiring adaptation in site choice, management practices, and species diversification.